Ever feel guilty about leaving work early?

As you sit there under the fluorescent lights and tap away at your keyboard, and think about how it’s dark outside and everyone else is at home having dinner… you can’t help but wonder: Why can’t you seem to just “finish this” and go home?

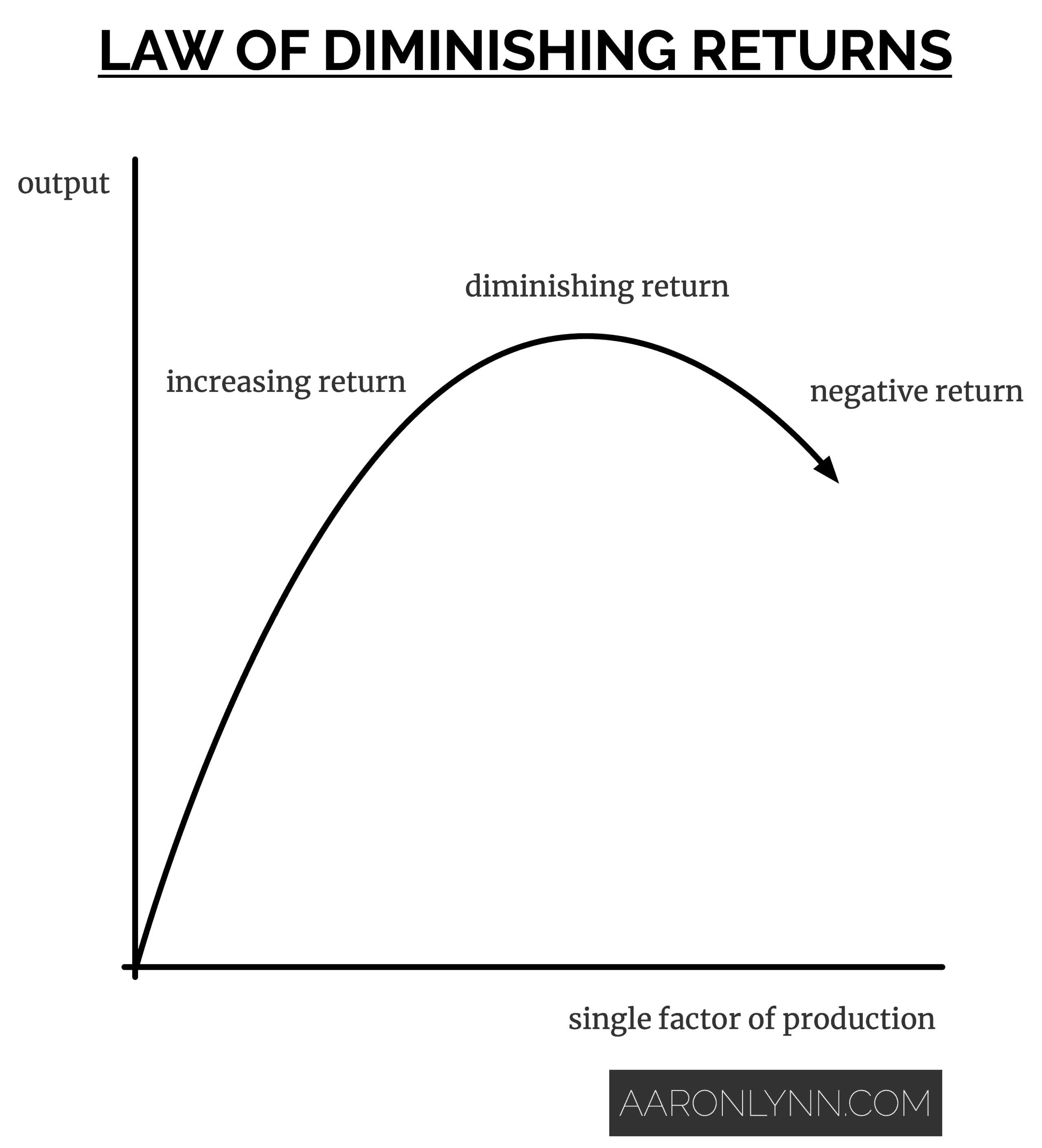

The reason we can’t complete what we are working on after hours of working on it, is because of the law of diminishing returns when it comes to our work and productivity.

Here’s how the law works and what we can do instead.

The Laws of Diminishing Returns and Diminishing Marginal Utility

The law of diminishing returns is where there is a decrease in the marginal/incremental output of a production process as a single factor of production is increased.

That’s the geeky systems definition.

A simple example would be using iron to make widgets.

As you input more iron, you don’t output widgets at the same pace — in fact, you output fewer widgets per unit of iron over time.

A personal example would be the work that we do. Putting more and more time into a singular piece of work without taking a break or doing anything else results in the quality (“output”) of that work going down. In other words, it’s really hard to produce meaningful work towards the end of an eight-hour cram session.

Why does this happen? Why do we get diminishing returns?

In economics, the standard explanation is that there are inefficiencies in the system, or overcrowding on the production line. The machine that turns iron into widgets only works so fast. If you keep feeding it iron, it can’t keep up.

A similar concept is the law of diminishing marginal utility. This is best illustrated with pizza 🍕.

If I give you a slice of pizza (🍕), you’ll get some enjoyment (“utility”) out of eating it.

And then I give you a second slice (🍕 🍕). You also enjoy that.

But then I keep giving you slices.

By your fifth slice (🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕) you are (hopefully) quite satisfied.

By your tenth slice (🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕) you’re starting to feel a little full and politely declining.

By your twentieth slice (🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕 🍕) you’re probably yelling expletives and asking if anyone else would like some pizza.

Your body’s ability to process and enjoy pizza goes down with each slice that you eat.

That’s the law of diminishing marginal utility, and for our purposes it is the same as the law of diminishing returns: you can’t keep adding time into something productive you want to do, and expect the same level of results or utility from it.

How the Law of Diminishing Returns and Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility Work in Productivity

When we talk about productivity and work we’re referring to the idea of a productivity stack, where you input resources, use leverage and process, and get productive output.

Say you’re writing something 📝.

Like the pizza, if you write for an hour that’s great.

A second hour is also great.

A third hour is probably OK.

A fourth hour is a bit meh.

By the fifth or sixth hour, you are likely writing drivel… which means you have to go back later and spend even more time correcting it.

This applies to almost any kind of work, not just writing.

I’ve seen it in both myself and in others who do knowledge work — artists, coders, content creators and of course, professionals.

You can’t just sit there and throw hours at something and expect to maintain any kind of quality output.

Here’s the systems explanation of why this happens in productivity.

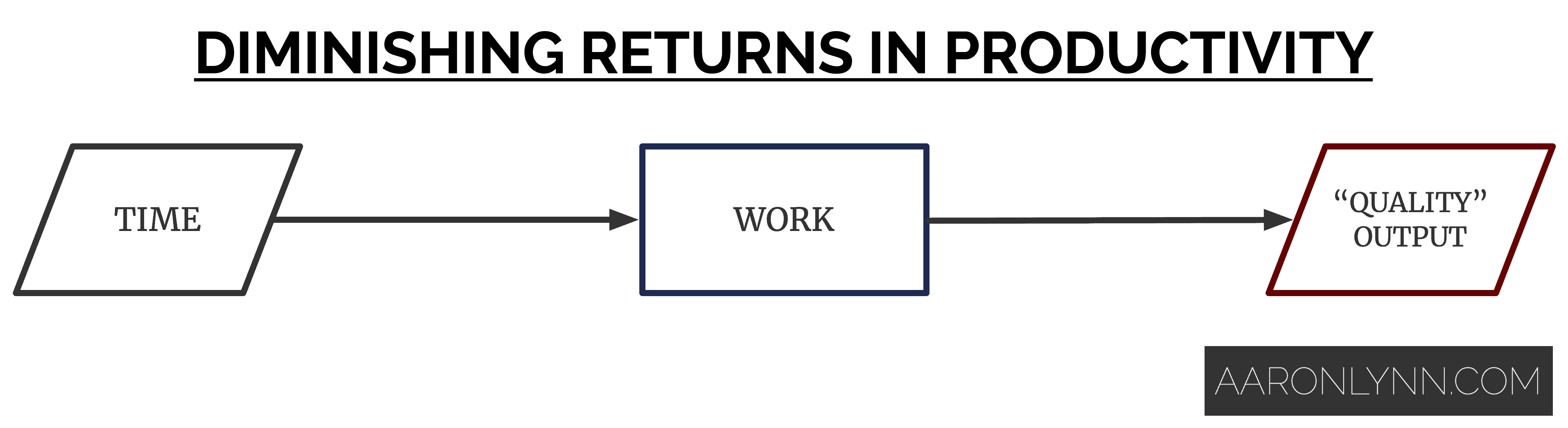

The input into our work-producing system is time. It is our “single factor of production”.

Our system processes this time to produce quality work. And as we input more time, we find out that our ability to produce quality work goes down.

This is because for something like knowledge work, there is more than one factor of production. We have to account for the other resources in the productivity stack, such as attention, energy and willpower.

We can linearly input time, but we cannot linearly input attention, energy and willpower. You need to stop and rest and recover those resources, which is impossible to do if you are working nonstop.

Here’s an oversimplified mathematical explanation.

For our first hour of work, if you input:

- 1 hour of time.

- 1 unit of attention.

- 1 unit of willpower.

- 1 unit of energy.

You output 1 unit of quality work as an average.

Now in your second hour, you have fewer of each resource, so you input:

- 1 hour of time.

- 0.9 units of attention.

- 0.8 units of willpower.

- 1 unit of energy.

And you output 0.93 units of quality work as an average.

That’s the law of diminishing returns applied to productivity. The more linear hours you put in, the lower the output of quality work becomes. Which means you’ll have to spend more time later editing and correcting your work.

What This Means for How We Work: Don’t Run Marathons

What this means is that our current cultural obsession with working insane hours, sucks.

Putting eighty, ninety, one hundred hours or more hours a week into work does not produce great work.

To borrow from sports, we are supposed to be sprinting and resting, not running marathons with our work.

I know.

We read about startup founders sleeping at the office and working one hundred hour weeks. And some of us work in companies where it’s expected that everyone stays back as late as the workaholic boss.

But most people don’t really comprehend the reality of working one hundred hours a week. One hundred hours a week is a little over fourteen hours a day. Here’s what it actually looks like:

- You can’t have a commute.

- You eat every meal at your desk or are on one meal a day.

- You probably won’t shower most days.

- You can only sleep about six hours a day.

- You basically live at your work desk. You’re sitting there from 9am to 11pm every single day.

- You need others to bring you a change of clothes, do your laundry, household chores etc.

Now barring a genetic mutation that lets you sleep only a few hours a day, most people cannot do this and still function.

This is not to say that you can’t work overtime and put in the hours when it’s needed. It’s saying that our societal expectation that people do this regularly is not realistic.

Yes, hard work is important.

And the raw hours you put into something are important.

But you are better off cutting hours from unproductive things and optimising the hours that you already put into something than simply putting more raw hours in.

How can we do this?

By treating our work as sprinting.

A Better Way to Work: Sprint and Rest

When it comes to modern day work, we are meant to act like sprinters, not marathon runners.

This means that we go hard — then we rest.

We focus on the outcome, not the output.

We get the important things done with quality, and don’t concern ourselves with the number of raw hours that we put in.

So what does sprinting and resting look like?

The idea comes from agile practices like SCRUM.

You may work hard for six hours in the morning, then take a break. And then you come back for a shorter second wind of three-to-four hours.

It means that you rest as you need to during the day, that you get enough sleep at night and you don’t stress over having to work every single minute of the day… or stay back late at work.

It means that you give your body time to recover the other resources you need to create quality work — attention, willpower and energy.

You can also apply the concept to longer timeframes.

If you’re working on a project with a fast-approaching deadline, you may put in the long days of say 8am-9pm in the office for a couple of weeks. But then you recover by taking a couple of days off when the project is over, and go back to a lighter 9am-5pm or 10am-6pm.

Optimisation and systems: More on sprinting and resting

If we want to go deeper into how we can make sprinting and resting work for us, we can optimise the time that we do spend sprinting.

This means we intelligently prioritise the tasks that we do based on the resources that we have available.

This means we do the hardest things or the things that require the highest quality output, first.

And we leave the things where we don’t really need large amounts of attention, willpower or energy for later.

For a modern knowledge worker, this could mean doing highly technical or creative work the first thing when they are their freshest, and leaving the administrative or “data entry” work for later.

We should also be using our systems as a form of leverage to help us sprint and rest.

This could be as simple as using a computer or code to help us identify errors — e.g., spell check or automated testing.

It could also be something like having another person review our work when we’re done with it.1This is a great practice for all companies to implement actually.

What To Do Next

You now know how the laws of diminishing return and diminishing marginal utility work with respect to your productivity.

You know that it’s OK to work hard, then take a break — and not feel guilty about it at all.

This means you can be more productive and less worried about having to work all the time.

And you know that when you are ready, you can sprint, rest, and then go deeper into prioritisation and using systems as leverage.

If you want to explore the concept of productivity more, you can read my guide to the productivity stack here.

If you want to explore the concepts of systems more, you can read my guide to systems thinking here or grab a free copy of Evolution here.

- This is a great practice for all companies to implement actually.

Photo by ivan Torres, Simon, Ray Hennessy, Suzuha Kozuki.